Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, Carnegie Hall, New York, N.Y., 1947, Library of Congress

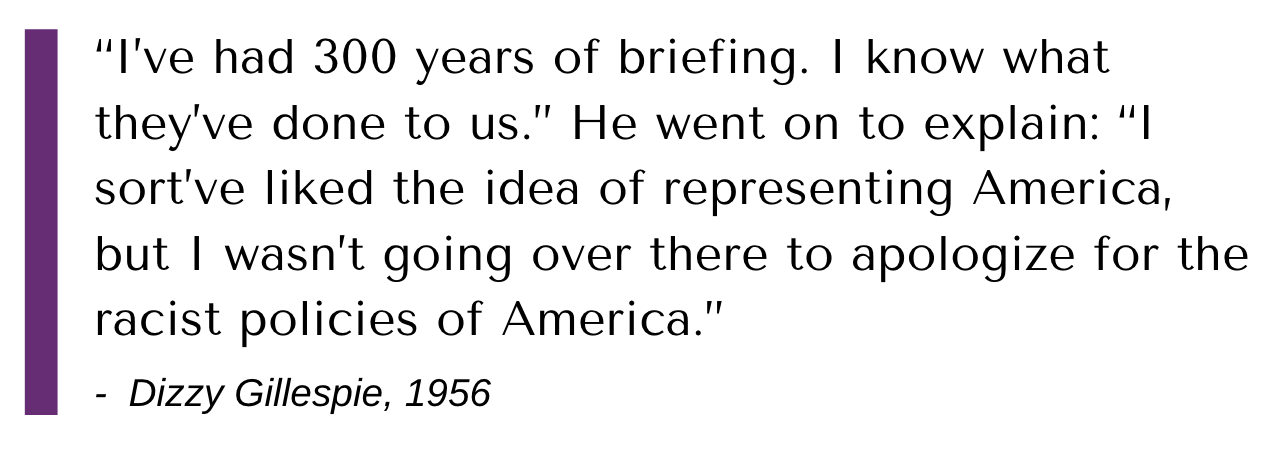

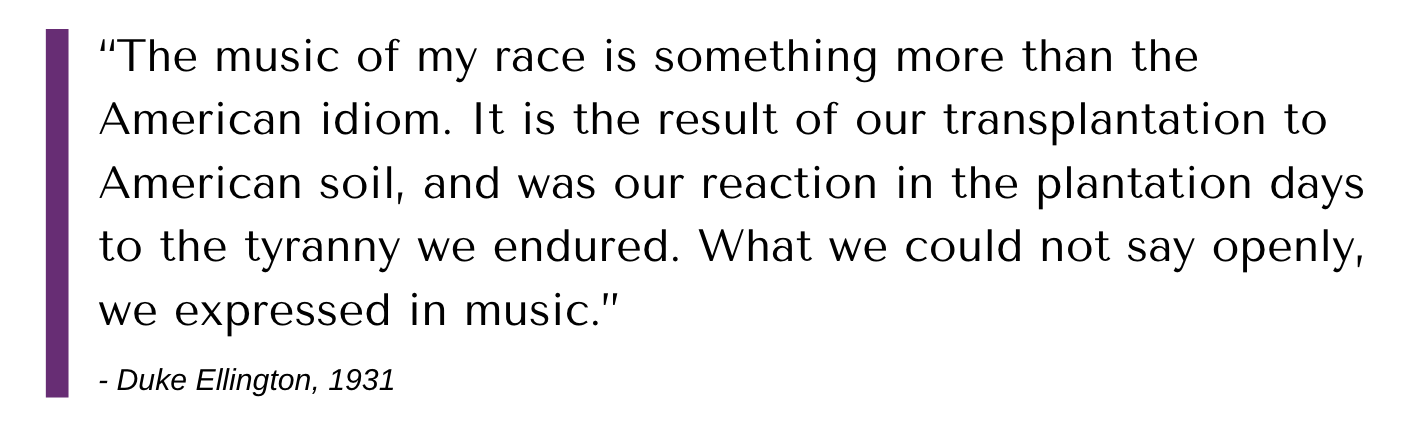

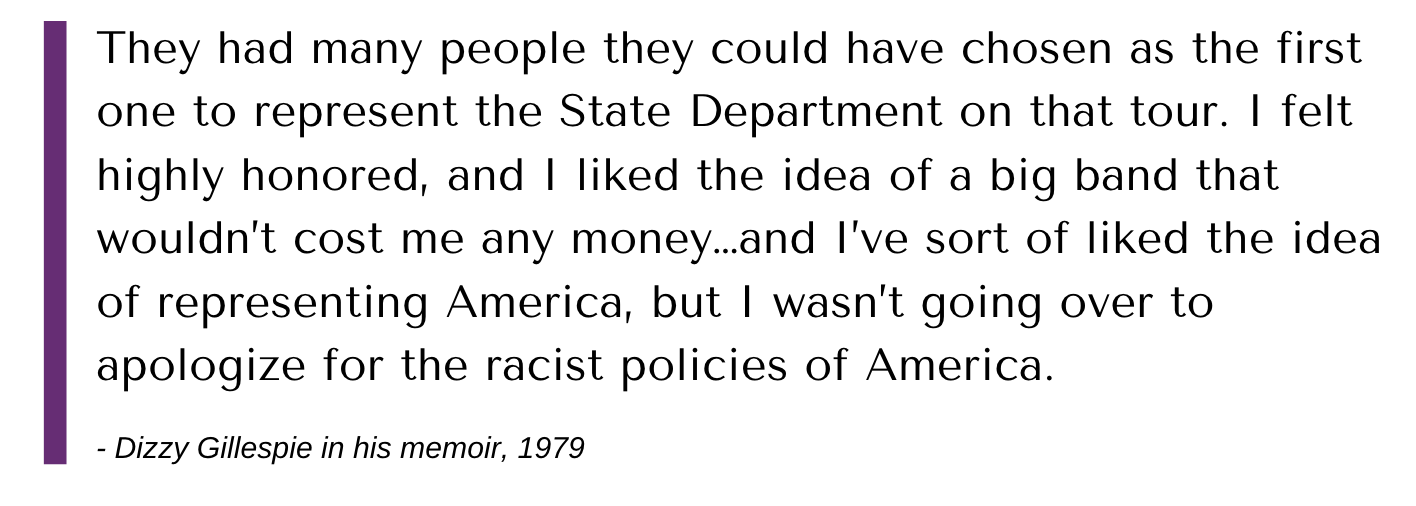

Yet African-American musicians were intimately aware of the hypocrisy of being sent to counter images of racism in America. The very same interracial bands which achieved success abroad could not perform in the Jim Crow South.

Dizzy Gillespie with Yugoslav Musician and Composer Nikica Kalogjera and Fans, 1956, Meridian Collection

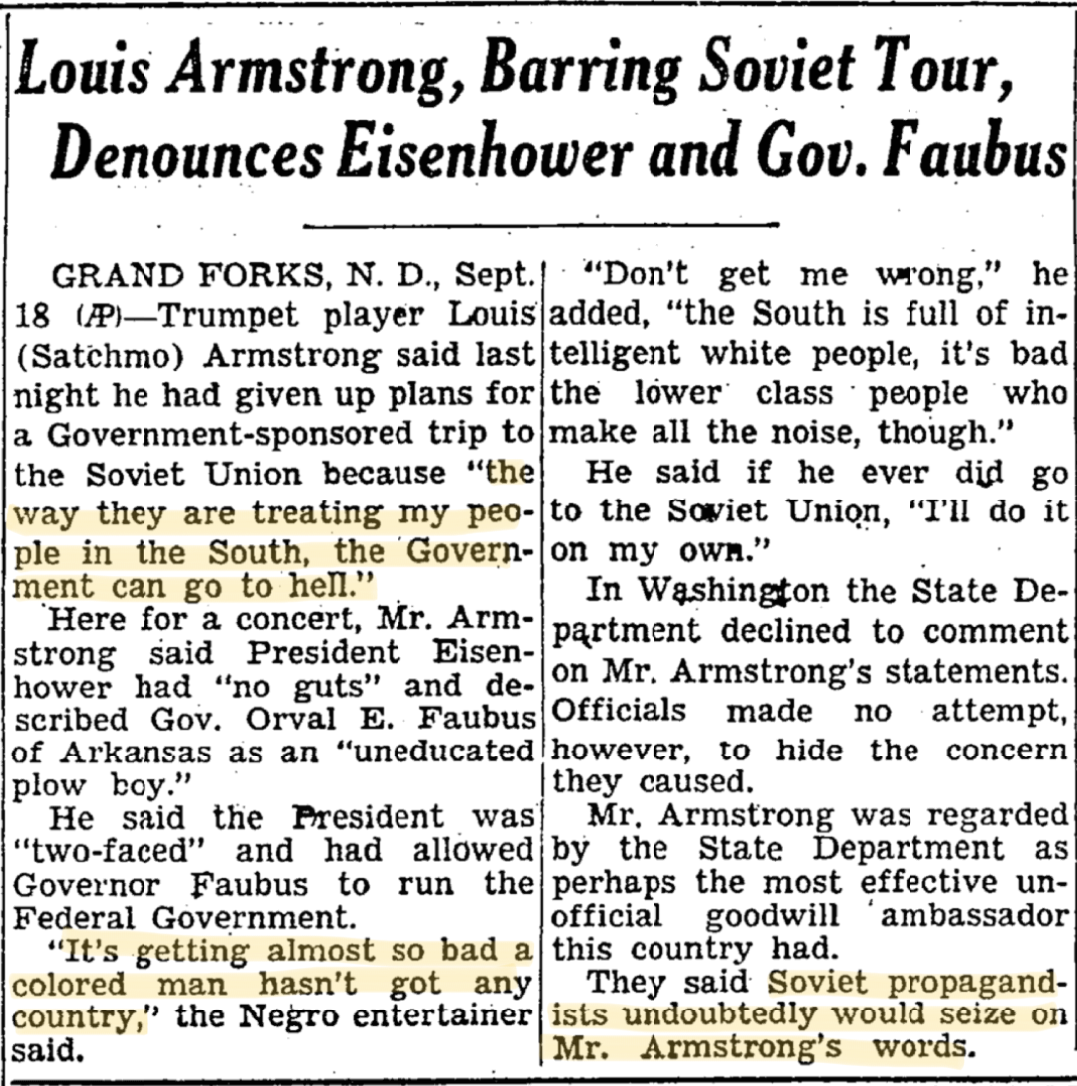

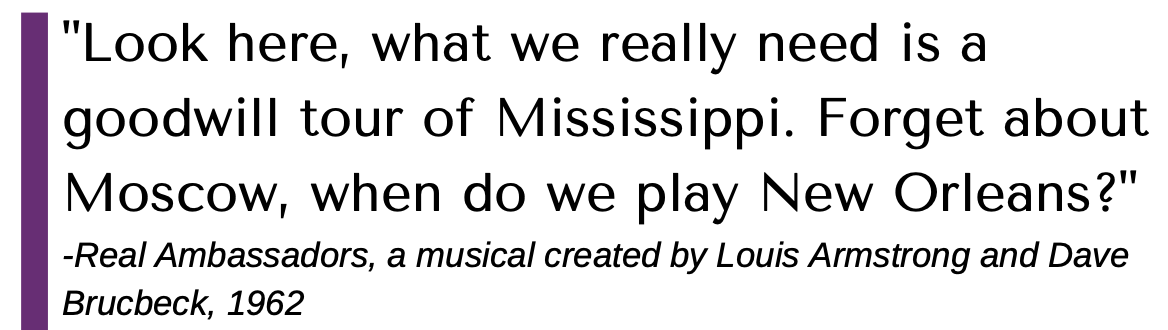

Many opinions emerged over whether African-American musicians should promote America abroad when equality was clearly denied to them at home. For instance, Louis Armstrong initially refused to participate in the program to protest government policies after Little Rock Nine.

New York Times, September 19, 1957

But many, including Armstrong, ultimately used the tours to earn recognition as African-Americans and as a platform to promote civil rights using their instruments for both peace and equality.

Dizzy Gillespie Playing, 1955, ABC-CLIO

And at home, the tours crossed racial frontiers as African-American musicians served as official representatives of the state while promoting an art from closely associated with black culture. The musicians wielded the soft power of the tours to spread optimism and instill black pride and respectability.

New York Times, November 7, 1960

Dizzy Gillespie Leads the First State Department Tour, 1956